In 2016, amid rumors of the illegal use of small hidden motors to enhance performance at the top level of the sport, the UCI seized one of the bikes of Belgian cyclocrosser Femke van den Driessche, the UCI's race mechanical The first case of doping was discovered.

According to L'Equipe (open in new tab), the National Financial Prosecutor's Office (PNF) concluded a multi-year investigation into mechanical doping at the sport's top level earlier this year without finding further evidence of mechanical doping.

Two financial magistrates, assisted by the French police's financial crimes unit, launched an investigation in 2017 into possible motor doping, rumored to have "benefited big-name riders and enabled them to take advantage of the latest technological advances in the electric motor field" at the "highest level." This was because a conspiracy was suggested.

According to L'Equipe, PNC investigators did not question former UCI president Brian Cookson, former general manager Martin Gibbs, or former technical manager Mark Barfield, but they did question Hungarian self-proclaimed inventor of the hidden motor Istvan Barjas was questioned.

On Twitter, Cookson mentioned a news article about the case's conclusion and said, "You'll have to allow me a wry smile about this... " he stated.

When asked why the testing was not done by an independent group, Cookson responded: "I'm not saying it doesn't exist. As I said, a system was put in place and we got someone. Some people say the system didn't work, but other systems have not caught anyone. The French authorities have investigated but say they have no proof."

[12Following accusations (vehemently denied by the Swiss star) that Fabian Cancellara used a motor to win Paris-Roubaix in 2010, the UCI began scanning bike motors with tablet devices; in 2015, under Cookson, the UCI issued a "technical cheating" and imposed harsh penalties of huge fines and bans of at least six months

for riders who committed such acts.

The UCI conducted thousands of tests, using tablets to scan bikes for a few seconds at the start and finish of races. However, none of this occurred until the 2016 UCI Cyclocross World Championships, when it was discovered that a spare bike in the pit area of U23 rider Van den Driessche had a motor on it.

Van den Driessche denied any knowledge of the assist motor, and a friend testified that the bike was his, but she was banned for six years.

In 2016, the UCI conducted 3,773 tablet tests and used thermal imaging cameras on the bikes and found no irregularities.

The UCI had hoped to deploy other technologies to detect motors, but L'Equipe reported that a partnership with the French Atomic Energy Commission (CEA) to develop a real-time bike-mounted monitor for evidence of motor magnetic fields has now been abandoned due to high costs

2018

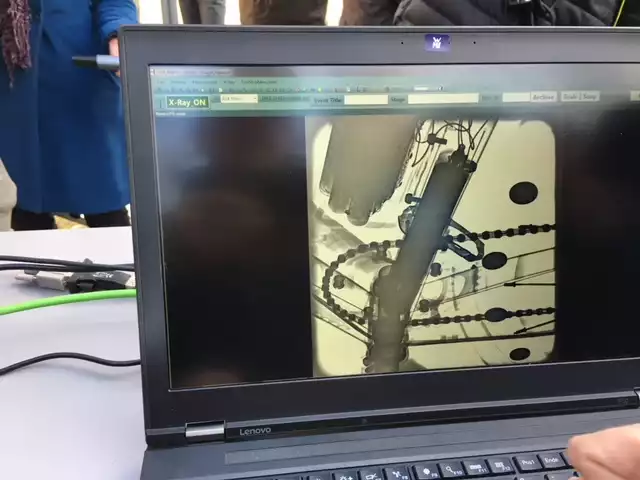

In 2018, the UCI added mobile X-ray scanner systems to its testing protocol. Small thermal cameras mounted on bikes during races were also used at the 2018 Tour de France, but this technology was also abandoned after false positives due to a mechanical defect in a rider's pedals.

According to L'Equipe, Jean-Christophe Péraud, a former rider and UCI "manager of equipment and the fight against technological fraud," told the French investigators that "99 percent certainty, he concluded that there is no hidden motor in the peloton."

It is unclear what, if any, international investigation was conducted. However, the French police decided to terminate the investigation. The only tests for mechanical doping are tablet devices and a few bikes (often those of riders selected for anti-doping) that are X-rayed at the race finish.

Comments