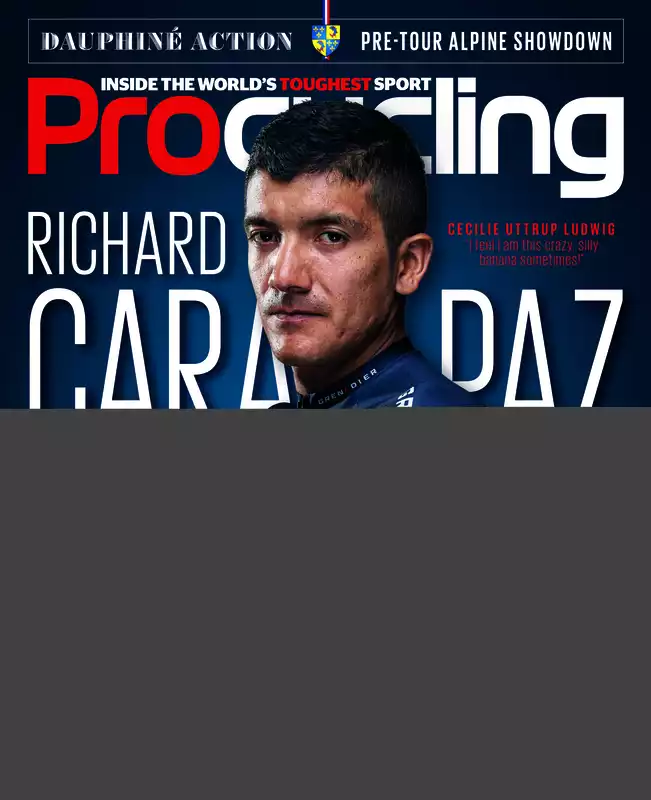

Procycling Magazine: Bringing you the best writing and photography from inside the world's toughest sport. Procycling Magazine brings you the best writing and photos from inside the world's toughest sport. Pick up a copy now at your local newsstand or supermarket, or sign up for a print or digital subscription to Procycling (opens in new tab).

Richard Calapaz's victory at the 2019 Giro d'Italia was historic for Ecuadorian cycling and the first Grand Tour win for the South American country. It may not be the last. Before Ineos Grenadiers' last-minute change in rider registration put the in-form Carapaz in the Tour de France squad, he had originally intended to defend his Giro crown.

The 27-year-old from El Calci, a 3,000-meter-high northern region adjacent to the Colombian border, was not only Ecuador's first Grand Tour winner and its first World Tour competitor, but also the first European-based professional in Ecuador's history. Meanwhile, Colombian professionals have been around for 50 years.

For Ecuador, Calapaz's victory in the Giro is a great milestone, as is roadwalker Jefferson Perez's gold medal in the 1996 Olympic 20 km walk, and Alberto' in the Copa Libertadores, the largest soccer tournament in South America during the 1960s and 1970s. Along with Cabeza Magica' (Magic Head) Spencer's soccer accomplishments, it is unofficially one of the country's three greatest sporting achievements.

So Carapaz's victory sounded like a sports fairy tale come true. But, he warns. [Ecuador is a country with a very short history of cycling. And for the general public, my sudden Grand Tour win seemed so random. They enjoyed it, but the memory of it is fading."

He also said, "I'm not sure if I'll ever be able to win a Grand Tour again.

He strongly argues that what little cycling culture there was in Ecuador, most of which remains centered in El Carchi, has steadily atrophied over the past decade thanks to the continued scarcity of public and private investment in the sport's future.

It is not only the junior and U23 cycling scene that is in trouble. Right now, Kalapas says, there are few professional races in the country. Last year, after a gap of four seasons, there was one UCI classified event, the 2.2-ranked Vuelta a Ecuador.

"There is no public support for the infrastructure of the few cycling clubs that exist. The government does not even have an organization to assist in the formation of new clubs."

The government has no support for the formation of new clubs.

This situation is hardly new. In an interview with the Ecuadorian newspaper El Tiempo last year, Karapas said that asking for state support for cycling is like "a cry for help to the deaf," but expressed hope that this would change. Judging from what he said, that has not changed.

The widespread indifference to the sport extends to public life in other, arguably more serious ways. One of the last things Carapaz did before heading to Europe this summer was to join a protest demanding justice for two Ecuadorian cyclists who were hit by a car while training, one injured and the other's brother killed. The driver was arrested but quickly released by police.

The saddest thing about this tough situation for cycling is that it is not hard to find interest and potential. At his school, his first and greatest mentor, teacher and former Olympic cyclist Juan Carlos Rosero, announced that he would open a club.

"That's how it happened, about 60 people joined," Carapaz said.

"The five European-based professional players that Ecuador produced - myself, the first professional player from my country, Honatan Narvaez from Ineos, Jonatan Caicedo from EF, and Androni and Caja Rural - all went to the same club in the same school.

This is an excerpt from an interview with Richard Kalapas in the October 2020 issue of Procycling magazine, on sale now.

Comments